Few people know it in Europe, but also in Japan : there is a domestic olive oil production on the Nippon archipelago ! Mainly concentrated in Kagawa Prefecture, and more specifically on the Shōdo Island, the crop arrived in the country more than one century ago, right after it opened its doors to the outer world. Here is a quick overview of olives crop in Japan, with Kubota Takeyasu, Director of the Shōdoshima Institute of Research for Olives, and Shibata Hideaki, chief researcher at the Institute and Head of its panel for olive oil sensory analysis.

Legend has it that the first Japanese person to ever eat olives was Toyotomi Hideyoshi, one of the three war lords who unified Japan at the end of the 16th century. King Philipp II of Spain is said to have shipped to him in 1594 a full barrel of salted olives, as a diplomatic present. The story doesn’t tell whether the noble warrior liked the gift or not. Anyway Japan shut its doors to the world a few years later, at the beginning of what became the famous Edo period (1603-1868).

This is only at the very end of this period that olive trees will cross again Japan’s road. In 1861, the last Shogun’s personal physician, who had the privileged opportunity to learn western medicine, suggested to explore olive oil’s therapeutic value. Olive trees were imported from France and planted nearby Tokyo, but they never gave any fruit.

In 1874, at the very opening of the Meiji period, the Japanese Red-Cross founder had new trees brought to Japan, from Italy and Greece this time. Those planted in Tokyo didn’t do better, however some of the trees introduced 500km south from the new capital gave fruits. The first olives ever born on Japanese soil !

The pivotal Russo-Japanese war

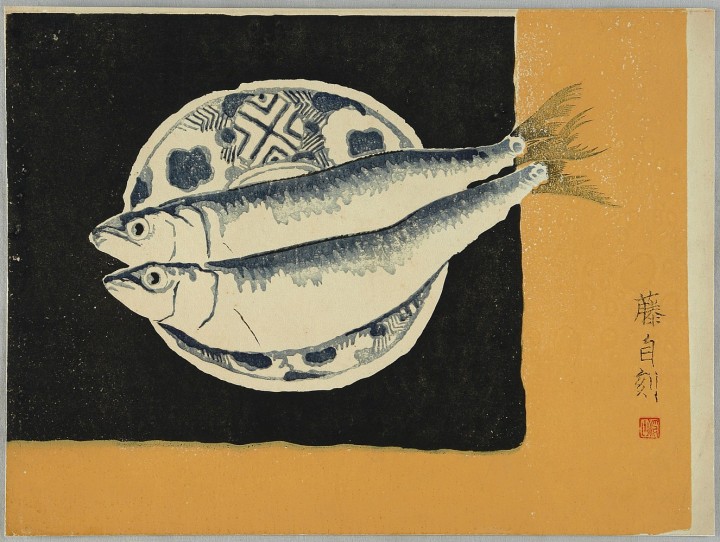

Experiments continued until the end of the 19th century, but with no over-zealousness. The shift is linked to Japan’s victory over Russia in 1905, as the Tsar has to give up several Northern Pacific islands to the Nippon Empire. And the fishing areas that go together. Tha Japanese fish production soars and more and more olive oil is required to put sardines in their can.

Weary of importing the precious liquid at high prices from Spain or Italy, the japanese government decides to revive the surveys on the viability of a domestic production.

After a preliminary study, 3 cities are selected in 1908 as experimental fields, amongst which Shōdoshima will be the only success. This is the beginning of a 111 years old history.

Ups and downs during the 20th century’s second half

After a boom in the 1950’s, thanks to the « japanese economic miracle » and the population’s fast growing standard of living, the olive oil domestic production decreased severely as of the 1960’s, mainly because of international trade agreements that allowed cheap european olive oils to conquer the (still rather small) japanese market.

At the turn of the century however, production starts growing again under the combined impact of a raising demand from the market on the one hand, and governmental subsidies on the other hand, for trees planting or mill acquisitions for example. But still today national production remains very low, especiyif you compare the numbers with importations (mettre lien vers article de synthèse Japon).

The role of Shōdoshima’s Olive Research Institute

Confronted to a brand new crop, which asks a know-how and special techniques, the olive farmers in Shōdoshima can rely on the Olive Research Institute, a public organization financed by the Kagawa Prefecture’s government (of which depends Shōdoshima).

For several decades the Institute, for which work nowadays 5 researchers and 2 agricultural technicians, has been experimenting and teaching all about things like soil maintenance, irrigation, pruning, fight against diseases, or of course harvest.

One of the great projects led by the Institute was the technical support provided to the farmers as of the end of the 1980’s to leave behind the stone mills and hydraulic presses, and adapt to brand new mechanized mills. Thanks to the help of the Institute and the subsidies from Kagawa Prefecture, more than half of the farmers in Shōdoshima have their own (small) mill.

Quite at the same time, at the end of the 1990’s, the Institute worked hard on settling its own sensory panel for olive oil. It is nowadays composed of 19 tasters àd has recently been recognized by the International Olive Council (IOC). Kubota Takeyasu and Shibata Hideaki have turned into fine olive oil tasters, regularly sought after for international competitions or panels.

As such experts, they managed to develop in 2013 a certification program for extra virgin olive oils produced in Kagawa Prefecture, despite the facts that COI’s international standards don’t apply to Japan and that the government’s official classification only distinguishes « virgin olive oil » and « refined olive oil ».

Thus, every olive oil produced in Kagawa Prefecture that meets the IOC’s extra virginity criteria will receive the Institute certification, which is a real guarantee of quality. A superior grade, called premium, is attributed to products that meet tougher criteria, and especially the free acidity level (a 0,3% maximum vs. 0,8% according to the COI).

The creation of such a label is at the center of the current strategy of the Institute to turn the market towards higher quality olive oils. By suggesting to the consumers a desire for premium olive oil, they could finally turn their back to cheap imported products that they like so much yet, because they are poorly informed and fancy the words « made in Italy » on the bottle.

A fight that is likely to take a lot of time, even if the passion of both the researchers is remarkable. And who knows, the 2 brand new, still top-secret and first japanese varieties that they have just developed in their lab will perhaps help them for this quest.